Recently the Ashley Leiman (Director and Trustee, Orangutan Foundation) presented a well received talk, entitled "Palm Oil Development and Biodiversity Conservation". Here is the message in brief, addressing the ever popular and confusing topic of Palm Oil within modern day orangutan and habitat conservation...

Some facts and figures...

- Indonesia is now the world’s largest producer of palm oil, and together with Malaysia, they produce over 80% of the world’s palm oil.

- This has brought major economic benefits to both countries. For example, according to CIFOR, in 2008, production of Crude Palm Oil (CPO) in Indonesia generated revenues of $ 12.4 billion dollars from foreign exchange exports and $ 1 billion dollars from export taxes;

- whilst employment generated directly by the palm oil industry in Indonesia in 2013 was estimated to be 3.2 million people.

Despite these major economic benefits, NGO’s have questioned the environmental and health costs involved. Of the 8 million hectares that are currently under oil palm in Indonesia, CIFOR estimated that at least half has been developed directly by deforestation.

The Indonesian Government hopes to expand the area under oil palm by an additional 4 million hectares so that the current production of CPO can be doubled to 40 million tons annually by 2020. This raises the questions: where will the additional 4 million hectares come from ?

Addressing the biodiversity of primary forests... Compared to oil palm plantations, how much biodiversity exists in primary forests? What options are available as a source of land to develop new areas for oil palm?

Koh & Wilcove (2008) showed that the number of species of birds and butterflies that were recorded in four locations... This shows that if primary forest is converted to oil palm, there is a 77% loss in forest birds, and an 83% loss in forest butterflies. It also shows that the 30-year old selectively-logged forest had largely recovered, to the extent that it contained 84% of the forest birds found in the primary forest.

So, secondary forests DO have the potential to recover all of the original biodiversity of their former primary condition... A review of studies covering a wider range of species by Fitzherbert and Danielsen have supported these results. They found an average of just 15 - 23% of forest species in oil palm.

From the biodiversity perspective, we can conclude that if new oil palm developments were to involve clear-felling existing primary or secondary forests to convert the land ready for planting with oil palm, this would result in devastation for the existing biodiversity, with an 80-85% loss of forest species.

What options are available? Where could there be a source of land to develop new oil palm plantations that do not destroy existing forest?

There is mounting evidence to show that there is already sufficient degraded ‘low-carbon’ lands that are suitable for oil palm, instead of converting existing forests. The World Resources Institute (WRI) has recently launched an initiative to map degraded lands in Indonesia. So far, WRI has identified more than 14 million hectares of such degraded lands in Kalimantan that may be suitable for oil palm production. Not all of this would eventually become productive, however, as some local communities may have alternative proposals.

In theory an area of State Forest Land that is released by the Ministry of Forestry for conversion to oil palm should not normally contain any forest, but the situation in practice is clearly different.

Many plantation companies report that they do have significant areas of forests within the boundaries of their concession. Taken together, these small islands of high biodiversity value provide an important compliment to the State’s total conservation land.

Speaking to people living and working in these areas...

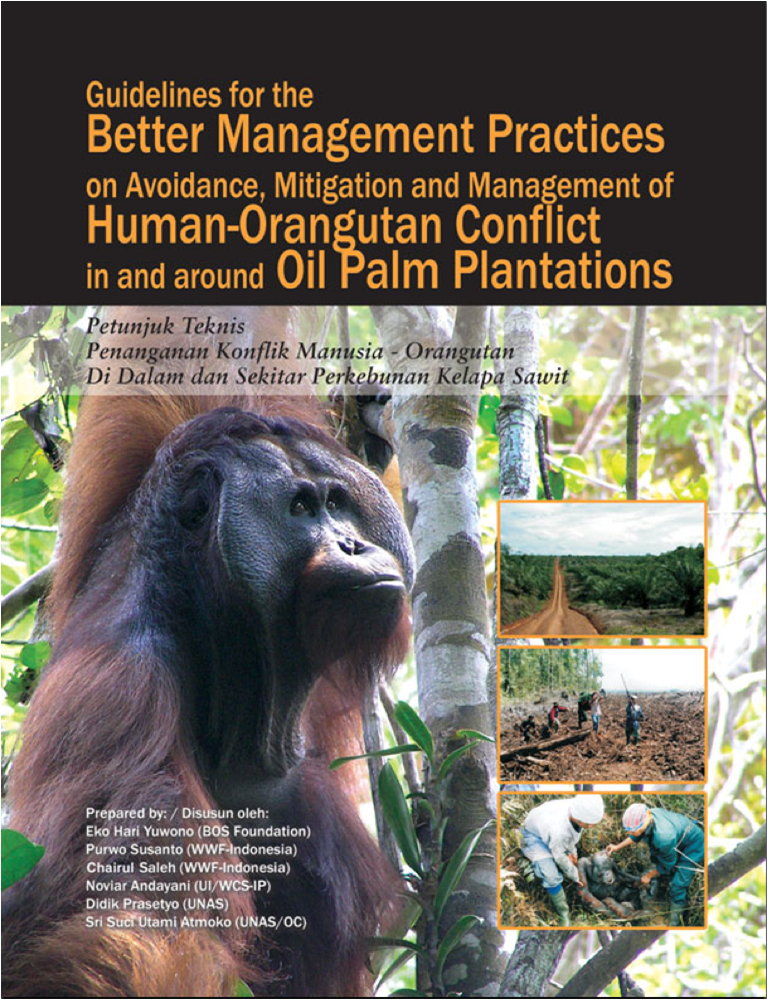

There is a growing conflict developing between orangutans and humans in and around oil palm. This is especially so in Kalimantan. Orangutans that have had their forest home destroyed are often found in remnant forest patches nearby, from where they enter cultivated areas and are labelled as pests. There have been some well-documented cases recently of workers from plantations companies or local communities killing orangutans.

Rescue orangutans from plantations and surrounding forest patches, although fantastic to remove individuals from degraded areas, also raises some problems. Primarily, for example, that given the massive scale of conversion of natural forests in Kalimantan to oil palm or other land-use development, there are not enough suitable forests that can take such an exodus of captured orangutans.

There are solutions...

- We need to change the perception of public and private sector stakeholders that orangutans they encounter outside conservation forests should be captured and sent to rehabilitation centres or relocated elsewhere;

- Plantation companies need to be persuaded to set aside high biodiversity forests within their concessions as locally protected conservation areas. This is allowed under current Government regulations, and hence compliant with ISPO criteria for certification.

- We need to raise awareness that there are alternative practical solutions, especially on how to deal with crop-raiding cases. Guidelines on this have been produced by a team from BOS-Indonesia, WWF-Indonesia and UNAS in 2007.

The Orangutan Foundation held a multi-stakeholder workshop. An important resolution was passed in which the participants committed to protect the orangutans within their concession and to exchange best practice experiences on mitigating conflicts with orangutans. To do this, the oil palm companies were urged to ensure they have a conservation plan to properly manage the biodiversity found in the remaining forests within their concession. This plan should be in accordance with the stipulations in the original environmental impact assessment (AMDAL) that should have been conducted before the Permit for Plantation was issued.

Palm oil certification on paper...

Great hope had also been invested in the RSPO as a means of producing palm oil without destruction of rainforests. Regrettably, the palm oil industry has not yet stepped up to the mark to achieve a majority of certified CPO, as currently only 15% of the CPO market comes from certified sources. In addition, there is growing concern that the RSPO’s certification process is not as rigorous as it should be.

This has prompted the establishment of a new group called the Palm Oil Innovation Group; whilst Greenpeace has urged progressive companies to go beyond the standards set by RSPO in their practices. It would be commendable, therefore, if the ISPO criteria included a ban on converting forests and had a stringent certification process.

Overall...

We hope the palm oil industry would consider using existing degraded low-carbon lands in Kalimantan, which have been identified as suitable for oil palm plantation, as this would provide an alternative land source for the industry in line with the Indonesian Government’s CPO target for 2020.

We believe this can this be achieved without further destruction of these magnificent rainforests and the spectacular biodiversity they contain. Help us via donating or finding out more via asking us anything at info@orangutan.org.