Bornean bearded pigs faced a massive decline from African swine flu, rarely seen in Tanjung Puting National Park since. However, recent footage from our camera traps has shown the species is slowly making a comeback!

Bursting with life - Mammals

Despite covering around 6% of Earth’s land surface, it’s estimated that tropical rainforests are home to 80% of our planet’s terrestrial biodiversity. These diverse forests are truly bursting with life, and within Tanjung Puting National Park and the Lamandau Wildlife Reserve in Indonesian Borneo, there are prime examples of this rich habitat.

During their work in the forest, our field teams spot orangutans and other primates in the trees, and yet they rarely see other Mammals as many tend to venture out at night. The elusiveness of many mammalian species in the forest means that the only time our team observe them is on remote camera traps or during wildlife rescues. Some of these fascinating species include:

Sunda Clouded Leopard - Neofelis diardi - Like orangutans, this species of leopard is native to the tropical forests of Borneo and Sumatra. Very little is known about the behaviour of these nocturnal and predatory cats due to their elusive nature, however we do know that their canine teeth are longer than any other cat species in relation to their body size, and their long tail helps with balance as they navigate through the tree tops and forest floor.

The main threat to these iconic forest cats is habitat loss; another trait shared with orangutans. Listed as 'Vulnerable' on the IUCN Red List, there are only an estimated 4,500 individuals remaining in the wild.

Sun Bear - Helarctos malayanus - This is the only bear found in South East Asia and the smallest of all the 8 bear species. Their smaller size means that they are perfectly suited to an arboreal life and their long claws and tongue are ideal for feeding on insects and honey in the trees.

The name ‘Sun Bear’ comes from the pale patch of fur on their chests which is said to resemble a rising or setting sun. Each pattern is unique like a human fingerprint, helping to distinguish one individual from another.

Malayan Civet - Viverra tangalunga - These small omnivorous mammals roam its forest habitat at night in the search for fruit, insects, and anything else it can find to eat. Although largely solitary, it's thought that civets use scent as a way of remotely communicating with one another amongst the dense vegetation by rubbing themselves on trees and the leaves on the forest floor.

Asian Small-clawed Otter - Aonyx cinereus - Rarely observed in the forest’s network of rivers as they tend to search for their food at night, these otters have extremely dexterous hands which are ideal at finding shellfish and crustaceans underwater. Through their high-pitched squeaks the otters can accurately locate one another, and it’s suggested that they can communicate using 12 or more different social calls. These are the smallest of all 13 otter species, but habitat loss and water pollution has impacted their numbers to the extent that they are classified as a species that is ‘Vulnerable’.

Yellow-throated Marten - Martes flavigula - Martens are members of the Mustelidae family (like weasels, ferrets, and badgers), and feast on a variety of food from lizards and bird eggs to fruit and nectar- thought to make them important seed dispersers in the forest. The yellow-throated marten is found throughout wooded areas of South East Asia, and their muscly build and long tail help make them as agile in the canopy as they are on the forest floor.

Malayan Porcupine - Hystrix brachyura - This is the largest of the seven porcupine species found in Asia. This species rely on their burrows to stay in during the day, and come out at night to forage for roots, seeds, nuts, and fallen fruit. Malayan porcupines appear to have strong family ties and will often travel in small groups searching for food. They may have few predators in this habitat, but when threatened, porcupines will often charge backwards in the hope that their sharp quills will deter any aggressor.

Bornean Bearded Pig - Sus barbatus - Like other pig species, the Bornean Bearded Pig is omnivorous and will feed on a variety of forest foods. Their long snouts are perfectly evolved to search for worms and tree roots under the soil, and they will also forage for seeds and fruit dropped by animals high up in the canopy. These pigs reach sexual maturity at around 18 months old and usually give birth to between two and four offspring at a time. Piglets have stripy coats to help them camouflage into their surroundings which fade in later life.

Deer - There are a variety of deer found in Borneo, the most commonly observed by our staff are muntjac or barking deer (below centre). With no wild tigers on this tropical island, and clouded leopards and humans being their only predators, deer can thrive in the forest feeding on vegetation. Lesser Mouse Deer (Tragulus kanchil, below left) and the vulnerable Sambar Deer (Rusa unicolor, below right) can also be found in another environment where the Foundation operates in Central Kalimantan, the Belantikan region.

Bursting with life - Birds

The diverse ecosystems within Tanjung Puting National Park and the Lamandau Wildlife Reserve in Indonesian Borneo are truly bursting with life. Our staff are fortunate to come across a variety of interesting species as they monitor orangutans in the field, conduct research, and safeguard the forest. Some of the most eye-catching species we come across are Birds, including:

Hornbills - There are 8 species of hornbill found in Borneo, and they are perhaps the most iconic birds found in the forests of this tropical island. Hornbills are infamous for the large casques on their beaks, the most eye-catching of which is the Rhinoceros Hornbill, Buceros rhinoceros. These impressive birds have brightly coloured beaks, can have a 50-inch wingspan, and typically mate for life.

Crested Serpent Eagle - Spilornis cheela - These raptors are found in various forest types and can survive in areas of disturbed habitat where other birds may not. In fact it could be said that these eagles prefer forest edges, where they can hunt for a variety of prey from snakes and lizards to small mammals and fish. This adaptability helps make them such a successful raptor species and they can also be found as far as India and the Philippines.

Asian Paradise Flycatcher - Terpsiphone paradisi - By looking at them, you could be forgiven for thinking that the male and female Asian Paradise Flycatcher are birds of completely different species, such is the contrast in their appearance. Females are modest-looking with black feathers on their heads and brown bodies, whereas adult males have bright white plumage and two enormous tail streamers. It’s thought these feathers are elongated to attract a mate and can grow up to 12 inches- longer than their entire body!

Storm's Stork - Ciconia stormi - This is sadly a species in decline and thought to be the rarest of all storks. Due to the loss of habitat in this part of the world, Storm’s Storks are listed as endangered on the IUCN Red List with fewer than 500 individuals remaining in the wild. These forests in Indonesian Borneo are a real stronghold for this vulnerable species so sightings of breeding pairs are vitally important.

Kingfishers - The easiest way for our field teams to navigate through the forest is via the network of rivers, an ideal habitat for kingfishers. The Stork-billed and Blue-eared Kingfisher (Pelargopsis capensis & Alcedo meninting) are the most commonly seen species in these forests. Stork-billed are perhaps the most striking as they have large red bills and an explosive alarm call which is then followed by an unusual cack-cack-cack-cack laugh!

This is just a selection of the hundreds of bird species found in this diverse tropical forest environment. By supporting our guard posts and habitat restoration programme, your help is ensuring that these important species continue to live in a haven which is protected.

Bursting with life - Primates

We may be the Orangutan Foundation, but our work also protects crucial forest habitat home to a variety of other ecologically significant species. It could be said that the forests we primarily operate in, Tanjung Puting National Park and the Lamandau Wildlife Reserve, are truly bursting with life.

These tropical forests are found in one of the most biodiverse corners of the globe in Indonesian Borneo, where Primates make up some of the most captivating fauna. Bornean orangutans are an umbrella species helping to protect habitat for a number of these arboreal mammals, but here are some of the other primates our field team study, monitor, and observe:

Proboscis Monkey - Nasalis larvatus - Perhaps one of the most unusual species found in the forest and indeed the primate world, proboscis monkeys can only be found in the wild on the island of Borneo. It’s thought that the elongated noses of the males help to attract females, and their round bellies containing two stomachs aid the digestion of leaves that other animals cannot eat.

These endangered primates live in close social groups, often in submerged and swamp forests. This means that sometimes they must swim between trees in search of food and to help them do this, proboscis monkeys have evolved partially-webbed hands and feet, making them expert swimmers and helping them avoid predators like crocodiles in the water.

Macaques - There are two species of macaque spotted by our team; the Pig-Tailed Macaque (Macaca nemestrina), and Long-Tailed Macaque (Macaca fascicularis) also known as Crab-Eating Macaque.

Some roam the forest independently in search of food, but the majority of macaques are found in flexible family groups. They always appear to be on the move and as such are one of the most commonly seen animals captured on our remote forest camera traps.

When it comes to their diet these primates are certainly not picky. Macaques are generally opportunistic omnivores and will feast on anything from leaves and seeds to invertebrates and eggs, it’s this versatility that makes them such a successful primate species around the world.

Langurs - These primates are also called ‘leaf monkeys’ due to their herbivorous diet. Comparatively little is known about their behaviour due to their elusive nature, but our team on occasion have spotted Silver Langur (Trachypithecus cristatus) and Red Langur (Presbytis rubicunda), also known as the Maroon Langur. It’s thought that the White Fronted Langur (Presbytis frontata) has also been caught on remote camera traps in the Belantikan region, another habitat which the Foundation help conserve.

Bornean White-Bearded Gibbon - Hylobates albibarbis - This is another species endemic to Borneo and listed as endangered due to the ongoing threat of habitat loss. Gibbons are neither monkeys or great apes, instead classified as ‘lesser apes’, but are perhaps the fastest primate when it comes to travelling through the canopy. It has been said that their long arms can swing them from branch to branch up to 34mph!

Gibbon pairs often mate for life and travel in small family groups. Each morning they will often strengthen this bond by singing a ‘duet’ which can resonate through the forest over a mile away, notifying other groups of their presence.

Western Tarsier - Cephalopachus bancanus - Also known as Horsfield’s Tarsier, these are the smallest primates found in Borneo. It’s understood that tarsiers are some of the oldest living primates, separated into 18 species which are all found in South East Asia.

Tarsiers are the only entirely carnivorous primates. Using their huge eyes to spot prey in the dark and then springing into action using their long legs, tarsiers feed on a range of nighttime creatures, primarily flying insects such as cicadas, moths, and beetles.

Bornean Slow Loris - Nycticebus borneanus - The large forward-facing eyes of the slow loris also indicate that they are a nocturnal species, perfectly adapted to hunt insects and small vertebrates in the trees.

They may look cute and cuddly, but the slow loris is the only primate known to have venom. Secreted from the brachial gland on their upper arm, it’s not fully understood why slow loris possess a bite which can be venomous. Perhaps this mysterious trait is why slow loris are regarded as the guardians of heaven in some local folklore.

Your support helps us provide a natural home to all of these primate species. Keep up to date on our work and subscribe to our monthly e-news updates to find out what other diverse wildlife species your crucial support protects.

Intimate images of crocodile mother and her newborn hatchlings caught on camera

Reptiles may not be considered the most maternal of creatures, but newly hatched crocodiles are in fact looked after by their mothers until they are strong enough to fend for themselves- often for as long as two years!

Our monitoring team located in Tanjung Puting National Park were fortunate enough to witness a mother and her nest using remote camera traps so as not to disturb her natural behaviour.

She was observed guarding the nest, listening to her young’s calls as they hatch, and then gently clearing a path for them to emerge from the undergrowth.

If you listen carefully, you can even hear the hatchlings calling from the nest.

Footage such as this is rarely seen, so to be able to use technology in order to witness this intimate behaviour without disturbing the animals is remarkable.

Once hatched and emerged from the nest, the young can be seen exploring their new home.

Hiding in plain sight: After a closer look, several hatchlings can be seen amongst the vegetation.

To be able see this behaviour is exciting for all of us, but also an indicator of the health of these important waterways. Watch this space for any future observations!

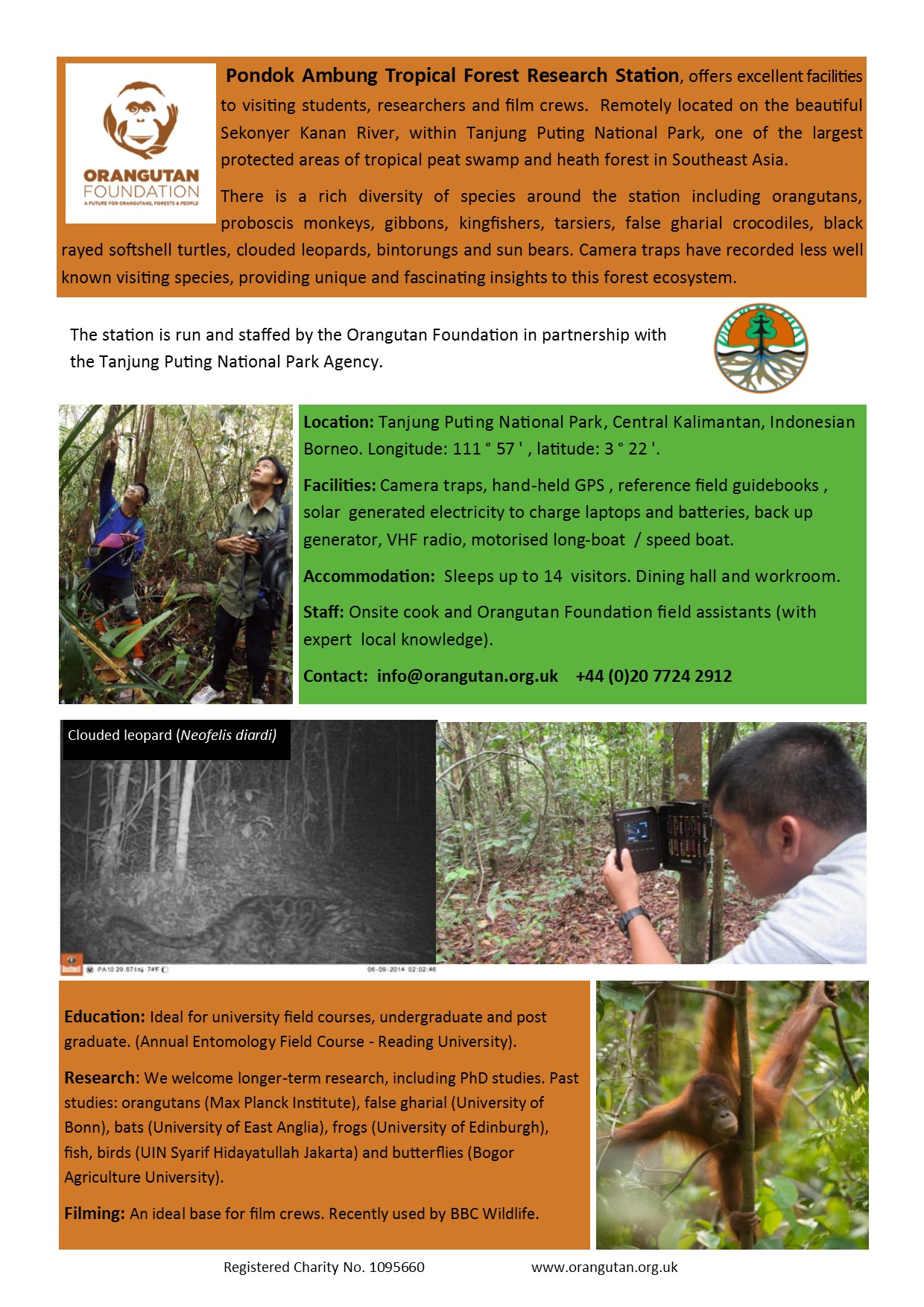

Researching fauna and flora in orangutan habitat, Indonesian Borneo

The tropical forests of Borneo and Sumatra provide far more than just a home for orangutans, they are one of the most biodiverse ecosystems on Earth. Our tropical forest research station, Pondok Ambung, is situated on the banks of the Sekonyer River in Tanjung Puting National Park, Central Kalimantan , Indonesian Borneo.

Camera trap snaps a wild adult male orangutan.

Orangutan Foundation researchers monitor and track the health of this ecosystem and the species found here. Our drive to promote tropical forest ecology and conservation to Indonesian students, winning their hearts and support, is crucial to the future of the orangutan and Indonesia’s forests.

This blog post provides a snapshot of some of the species studied and the activities undertaken at Pondok Ambung this year. As you will see, many take place after dark.

Students from school SMAN 1 Pangkalan Bun on a forest night walk looking for signs of wildlife.

Bornean Tarsier (Tarsius bancanus boreanus). A nocturnal primate found at Pondok Ambung Research Station, Tanjung Puting National Park, Indonesian Borneo. March 2019. Researchers also detect their presence by the scent of their urine.

Orangutan Foundation researchers fitting camera traps, which require constant maintenance in the humid conditions and with the odd interference from wildlife too!

Introducing high school students to camera traps.

Pig-tailed macaque (Macaca nemestrina) known locally as monyet beruk

False gharial crocodile (Tomistoma schlegelii) can reach more than 5m in length.

Two excited crocodile researchers! Orangutan Foundation support their studies with a research grant.

Individual crocodiles are tagged and monitored.

Local high school students using traditional and new ways to identify species.

Phenology studies. In March, observations along a transect found 25 species of tree flowering and fruiting, many orangutan food trees such as papung and ubar.

Squirrel - feeds on fruit and nuts and can help to spread seeds when accidentally dropping them whilst gathering and carrying.

Caught on camera, but who did it? Orangutan, bear, deer or pig?

Camera traps are a window into the fascinating and private lives of wildlife. Maintaining and keeping the cameras working in the hot humid and damp conditions of a rainforest is an ongoing challenge. Battling the elements is something our researchers are prepared for but they were shocked to find that one of the camera traps had been severely damaged, torn apart and discarded broken, 2 meters away from its original position. Who had done this?

Damaged camera trap

What the culprit hadn’t realised was that the data before the incident was undamaged and so our researchers could look back and see who had been out and about! Their suspects were orangutan, sunbear, deer and wild pigs.

Orangutan

Sun bear

Was it a deer?

Wild pig

On closer examination there were bite marks on the camera and it had been pulled off the tree. A sun bear could pull it off but there weren’t any claw marks and these would be evident. We suspect it must have been an orangutan. They are a highly intelligent and curious species and this is why it probably wanted to inspect the unusual device it found in its forest home. This is alone is a reason we need to continue to find out about them and work to conserve them.

The future of conservation is in our hands

The survival of the critically endangered orangutan and its forest habitat lies in the hands of Indonesia's youth. Their opinions, decisions and actions will determine its future existence in the wild. This is why awareness and capacity building is vital to the long-term conservation of this threatened great ape.

This month the Orangutan Foundation, and other local organisations, delivered a series of lessons to senior school, SMAN 3 Pangkalan Bun (Central Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo). Our Research Manager, Arie, talked about the importance of research and our work at Pondok Ambung Research Station in Tanjung Puting National Park. The Orangutan Foundation's Forest Patrols Manager, Jakir, led an inspiring session about photojournalism.

Why is Pondok Ambung Research Station important?

Every few months our staff move camera traps to a different location within the research study site. Just some of the wildlife documented so far includes clouded leopards, sun bears, muntjac, crested fireback (forest pheasant), mouse deer, tree mouse, frogs and pig tailed macaques.

They also monitor tree phenology, recording which species of tree are in flower or fruiting and which consumer species are feeding from them and how often.

Our research station was renovated by last year’s volunteer team and is now much better equipped to hosted visitors. In January, 65 students visited. The students participated in wildlife observations, learnt field skills, watched and discussed a wildlife trade documentary and planted 500 tree seedlings, at Pondok Ambung’s forest restoration site.

The success of the event was due to the collaborative efforts of Orangutan Foundation staff and other organisations including; Bagas the Traffic / IUCN Redlist Ambassador for Kalimantan; Fajar from OFI, the FNPF, BTNTP and FK3I. The event was supported by the National Park’s tour operators and guides who provided a free klotok (longboat) as did FNPF.

Please donate to support our work - it is needed to secure a future for oranguans, forests and people. DONATE HERE

Have your donation doubled for free and support Borneo's wildlife conservationists

From 28th November until 5th December you can DOUBLE your donation through the Big Give Christmas Challenge, at no extra cost to yourself. Click here to donate and double your impact to support our work. This year our we are raising funds to inspire Borneo’s future conservationists. In this clip Arie, Research Manager of Pondok Ambung, our tropical forest research station in Tanjung Puting National Park, explains why it is important.

We use camera traps to monitor the wildlife in the forests surrounding Pondok Ambung. Watch this short clip to see some of the species we’ve managed to capture on film!

To protect Indonesia’s biodiversity, future conservationists need to be encouraged and supported.

Our research station is a base from where Indonesian students and international scientists can conduct research. Take a virtual tour below:

Please help us to ensure a future for orangutans, forests and people.

Thank you for your support. Click here to DOUBLE YOUR DONATION through the BIG GIVE.

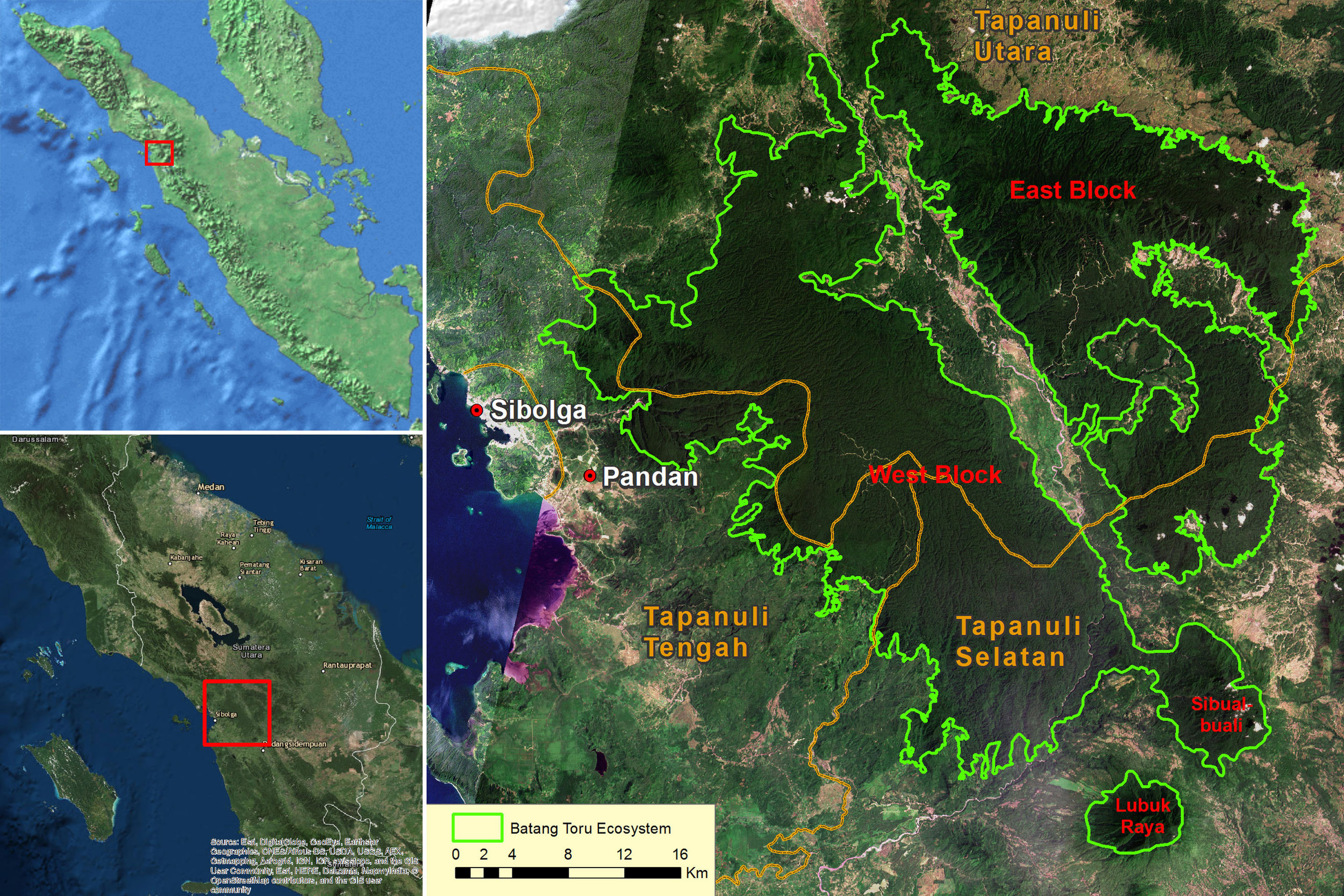

The Tapanuli orangutan, a new species known to science

Yesterday brought the extraordinary news that a new orangutan species in Sumatra has been officially recognised by a group of scientists (for full paper, click here).

The Tapanuli orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis) has been found in the Batang Toru Ecosystem of North Sumatra, Indonesia. Until recently these orangutans were thought to belong to the genus Pongo abelii, also known as the Sumatran orangutan. However, research has revealed that genetically, these orangutans are more closely related to Pongo pygmaeus, the Bornean orangutan, but remain distinct enough to be classed as an entirely new species.

There are a number of genetic, morphological and behavioural differences between the Tapanuli orangutan and its cousins. Interestingly, the Tapanuli male's long call is just one of these differences...

A Tapanuli male orangutan's long call (credit SOCP):

[audio wav="http://www.orangutan.org.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Togos-LC_036.wav"][/audio]

A Bornean male orangutan's long call:

[audio mp3="http://www.orangutan.org.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/longcall2.mp3"][/audio]

Other differences which have been recorded include their diet, skeletal structure, and hair, which is thicker and frizzier than that of the Bornean or Sumatran orangutan.

Sadly, despite being the newest species of great ape known to science, they have immediately been classified as critically endangered, with only 800 individuals thought to exist in the wild. Their only threat is habitat loss. The Tapanuli orangutan’s range is already fragmented across three areas of forest. Additionally the area is threatened with the proposal for construction of a new hydrodam.

Therefore, we must ensure further loss of their forest habitat is prevented. Visit http://www.batangtoru.org/ for further information and to help this new species.

Thank you,

Orangutan Foundation

Q&A with the Programme Manager of the Orangutan Foundation

People's Trust for Endangered Species (PTES) have been supporting the Orangutan Foundation's work in Indonesian Borneo for a number of years. We would like to share this Q & A with PTES and our Indonesian Programme Manager, Ade Soeharso, as part of the launch of their new appeal to save orangutan habitat.

Orangutan expert and Programme Manager at the Orangutan Foundation, Dr Ade Soeharso, answers some questions about the lives of orangutans, the dangers they are facing and ways anyone can save them now.

When did you start working at the Orangutan Foundation?

I’ve been a partner of the Orangutan Foundation since 2006. I was still working for the government then. Between 2008-2014 I worked part-time as a technical advisor of the Orangutan Foundation, and since 2015 I’ve worked full-time for the Orangutan Foundation.

What is the ideal habitat for an orangutan?

The ideal orangutan habitat is a mixture of swamp forest, lowland dry forest, and mountain forest. Ideally the habitat would be undisturbed and have an abundance of trees for food and nesting.

What is a protected forest?

In Indonesia, a protected forest is a one where the underlying area is protected from being logged or converted to other uses by land clearing.

What is palm oil? Why is the production of it so destructive?

Palm oil is a vegetable fat produced from oil-palm fruit. Almost all food products and many other common items use palm oil as a raw material. Therefore, palm oil is produced in large quantities because there is a huge market. Unfortunately, production of palm oil requires very large areas and which is achieved by cutting down large numbers of trees, which we call forest conversion and land clearing.

What have you found the hardest thing about working on the project so far?

The conservation of forests and the animals that depend on them is still often seen as less important than economic and development issues. It is challenging to mobilize the support of the parties in forest conservation efforts.

What is causing conflict between wildlife and the human population?

Due to deforestation, the amount of wildlife habitat left is ever decreasing. This means that the potential conflict between humans and orangutans will only increase. Orangutans and many other animals such as crocodiles, bears, and monkeys are forced out of the degraded forest and end up in community settlements and plantations in search of food. Seen as pests, they are often shot. We make sure that where possible, wild animals are translocated back into safe habitat. This is only possible if there is safe habitat left to move them back to.

What do you enjoy most about working with orangutans?

I enjoy it so much when I could see orangutans who have been rescued and then released growing and thriving in well-preserved habitat, successfully raising families of their own.

What time do you have to get up in the morning? Are orangutans early risers?

I get up early at 5:30 am. In the forest, orangutans rise between 5:00-5.30 am and leave their nests to set off in search of food.

How do you manage not to get lost in the forest when you’re following apes?

Basically, when following apes we’re never alone. There are always at least two people. As well as helping record data and times, they are locals who are more familiar with the forests so that we don’t get lost.

How many orangutans have you and your colleagues saved recently?

In 2017, so far we have saved 14 orangutans. Some of them have been released already as they are mature and well enough. The others are in the soft release programme. They are taken out into the forest each day to practice feeding and climbing until they have mastered the basic skills and are ready to be released.

Are you optimistic about the future for orangutans?

I am optimistic that orangutans can still be saved as long as we focus on saving their forests that are an integral part of their lives.

What must happen to ensure their survival?

We have to encourage the creation of sustainable oil-palm plantations and stop forest conversion in orangutan habitat and prevent the occurrence of forest fires. We also have to ensure that law enforcement act so that no more orangutans are traded as pets.

What can our supporters do to help?

As well as donating to this project, if you are buying a product that is made using palm oil, look out for ‘sustainable palm oil’ on the label. Currently, the global area already being used for oil palm production is sufficient to meet our needs without any further loss of forest. It is possible for us to use oil-palm produced from sustainable palm oil plantations and it is something we can all to do.

Please help us to help orangutans today so that they are still here tomorrow.

Indonesia's future wildlife conservationists

Orangutan Foundation hosted 53 visiting Indonesian students from Bogor Agricultural University in June.

Ashley Leiman OBE, Orangutan Foundation Director, greeted the students at our research station in Tanjung Puting National Park, Central Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo). The students were studying Silviculture. The name comes from the Latin silvi meaning forest and culture as in growing.

Providing opportunities and the facilities for Indonesian students to study tropical forests is not only vital for the future of the country's forests and people but is for orangutans too. A recent article in the journal Nature Scientific Report stated that 'Orangutan populations on Borneo have declined at a rate of 25% over the last 10 years'. If we are to truly tackle this problem we have to think long-term. The future of orangutans ultimately rests in the hands of the Indonesian people.

Please donate to support our work - a future for orangutans, forests and people.

Thank you,

Orangutan Foundation

Research and the Rainforest

Research and the Rainforest To mark #RainforestLive2017, we explore the reasons why rainforest research is so critical to our operations in Indonesian Borneo. We share recent research on individual species, and an overview on other more general research which is ongoing.

Research provides the basis for making key decisions on the conservation of rainforests. Since 2005 the Orangutan Foundation has managed a tropical forest research station, situated on the Sekonyer river inside Tanjung Puting National Park, Indonesian Borneo. Known as Pondok Ambung, it is used by international researchers, Indonesian students and university groups for wildlife and forest research.

Recently the field staff stationed at Pondok Ambung have been carrying out research on tarsiers, a species of primate, and false gharials (T. Schelegelii), a species of crocodile. These two species are found within Tanjung Puting National Park and both are threatened with the risk of extinction in the wild. Little is known about either species. It is important to learn more about their behaviour to learn how best to protect them.

You can learn more about our tarsier research here.

Field staff have been monitoring false gharial activity on the Sekonyer River, in Tanjung Puting National Park. Four have been caught and tagged in areas close by to Pondok Ambung, so that staff can monitor their behaviour long-term.

We also received exciting reports of the presence a very large false gharial in the area judging by the size of its footprint (twice the length of a pen!).

However, staff did not come across the creature during the survey.

Staff also conducted interviews with miners outside the park, who also reported sightings of 7 large false gharials in the surrounding area. More research will be conducted on why these crocodiles are living in areas of human disturbance such as this, but it is likely a result of a higher abundance of food.

Alongside recent research on individual species of wildlife, we also have a number of camera traps placed around Pondok Ambung in order to monitor the biodiversity of the surrounding forest. Watch this short clip to see some of the species we’ve managed to capture on film:

All this data provides important insights into the biodiversity which exists within the area we protect. It is vital we learn as much as we can in order to help protect and raise awareness of the important role each species plays in the rainforest ecosystem.

This is why the Orangutan Foundation takes part in events like Rainforest: Live, joining a global movement to spread the word and encourage action to protect the incredible biodiversity that exists within tropical forest habitat.

Follow us today on social media, using the hashtag #RainforestLive!

The Orangutan Foundation's 5 Programmes in Indonesian Borneo

Watch this short video to learn about our 5 ongoing programmes in Indonesian Borneo:

Please help us ensure a future for orangutans, forests and people. To support our work with a donation, please click here.

Thank you.

#WildlifeWednesday: Tarsiers

The Orangutan Foundation manages a tropical forest research station in Tanjung Puting National Park, Indonesian Borneo.

Pondok Ambung Research Station is used as a base from which our field staff, students and international researchers can learn more about the flora and fauna of Borneo’s forests.These studies are vital when implementing strategies to best conserve rainforest habitat in this area.

Pondok Ambung Research Station is used as a base from which our field staff, students and international researchers can learn more about the flora and fauna of Borneo’s forests.These studies are vital when implementing strategies to best conserve rainforest habitat in this area.

We’ve just received an exciting report from our research manager on tarsiers.

TARSIER FACTFILE

- There are 10 known species of tarsier, all of which are found in Southeast Asia.

- Tarsiers are the only carnivorous primate, primarily feeding on insects, but have been recorded to feed on small birds, bats, frogs, crabs and even snakes!

- Tarsiers are small primates, averaging around just 13cm in length.

- They are nocturnal, using their large eyes and ears to hunt for prey at night.

- Their spines are specially adapted to allow them to turn their heads nearly 180° in each direction, perfect for locating prey.

- Tarsiers move by leaping; Bornean tarsiers have been recorded to jump distances over 5m!

- They are sexually dimorphic: males are larger than females.

- Tarsiers have been known to live for up to 16 years.

- They are generally found no higher than 2m above the forest floor.

- They tend to live in small groups of around 3 individuals.

- Tarsiers mark their territory with scent – using their urine!

A Tarsier is a primate which inhabits a range of different forest types. Their taxonomic classification is as follows:

|

ORDER: |

PRIMATES |

|

SUB ORDER: |

HAPLORRHINI |

| INFRA ORDER: |

TARSIIFORMES |

| FAMILY: |

TARSIDAE |

| GENUS: |

TARSIUS |

The species our staff studied is known as the Bornean Tarsier (Tarsius bancanus boreanus). Bornean tarsiers are widespread throughout the island of Borneo. Listed by the IUCN as “Vulnerable”, Bornean tarsiers are threatened by the risk of extinction in the wild, as a result of habitat loss.

A population exists within the forests of Tanjung Puting National Park. Our field staff have conducted surveys to track this lesser-known species of primate. Locations where tarsier activity was identified were tracked using GPS. Our staff directly encountered two tarsiers, with 10 other indirect encounters from identifying their scent - left with urine.

All traces of tarsiers were found either near the river or in swamp forest, as this is where tarsiers obtain most of their food. Supporting other research, the two tarsiers spotted were found only in small trees, no higher than 2m from the ground.

Field staff reported heavy rain during tarsier observations, which made it difficult to spot and follow them in the dense vegetation.

It is vital we conserve these types of habitat for tarsiers by preventing human activity in this area of protected forest which leads to habitat loss. Limiting the amount of tourism in this area would also be beneficial so the area can be better managed.

Want to learn more about our research programme? Watch this short clip:

The Forest - A Message of Thanks

We have just received a wonderful message from our Research Station Manager, Fembry Arianto. The Orangutan Foundation manages Pondok Ambung Tropical Forest Research Station, which lies within one of Southeast Asia’s largest protected areas of tropical peat swamp and heath forest, Tanjung Puting National Park, Indonesian Borneo.

"The Forest…the place where I can rest, think, learn, observe and create my future…thank you to all my colleagues who always give great support and work together so well.

Today marks 3 years and 21 days of working for the Orangutan Foundation, I’ve given and received so much from this organisation…thank you for everything, the passion runs deep!"

There is a rich diversity of species around the station including orangutans, proboscis monkeys, gibbons, kingfishers, tarsiers, false gharial crocodiles, black rayed softshell turtles, clouded leopards, bintorungs and sun bears.

Pondok Ambung is available for use by individuals wishing to conduct research within Tanjung Puting National Park.

Pondok Ambung is available for use by individuals wishing to conduct research within Tanjung Puting National Park.

For more information please get in touch with our UK office info@orangutan.org.uk.

All photos show the grounds and variety of wildlife which can be found around Pondok Ambung Research Station, taken by Orangutan Foundation staff.

Scientific research grants from the Orangutan Foundation

The first research grant was given back in 1993 and since then we've supported projects that have varied widely on the species of Central Kalimantan. Projects have ranged from research into the biodiversity of fish in the Tanjung Puting National Park river , to groundbreaking orangutan behavioural projects. Some of these behavioural projects were the starting point to various research that is now full time. Indeed, many of our grant recipients have gone on to establish themselves as full time researchers and professors!

Recently, the grants have been given solely to Indonesian students, increasing the way in which the Orangutan Foundation support and work with local communities to save biodiverse habitat, including the home of the glorious red ape. Recent studies include looking into the mating habits of proboscis monkey. This renowned species is classed as endangered, living along the riversides in the Tanjung Puting National Park and threatened by many of the same threats which are contributing to the decline of wild orangutans. In the past decade, we funded the study of the feeding behavior and estimated home ranges of released orangutans in the Lamandau River Wildlife Reserve which we protect. This information is vital to all organisations who release orangutans to understand what fruit and types of habitat are preferred by rehabilitated individuals. If rehabilitated individuals remain unstressed when reintroduced to the wild - due to good quality, well chosen habitat - their chance of survival is greatly increased. For other titles of research projects, please see our website here...

Many of the projects are based at our research station - Pondok Ambung (please click) - located within Tanjung Puting National Park, sitting off the side of the beautiful Sekonyer Kanan black-water river. This station is newly refurbished with perfect facilities and dedicated staff-team to ensure any research conducted becomes an informative and enjoyable project! This national park facility has been developed and maintained by the Orangutan Foundation and was designed for visiting researchers to come and study the park’s diverse flora and fauna.

We are excited to see what future research will be supported by the Orangutan Foundation. As projects discover more and more, they also always contribute to protecting those all important areas for Indonesian's biodiversity to flourish.

Thank you for any support toward Orangutan Foundation's research projects!